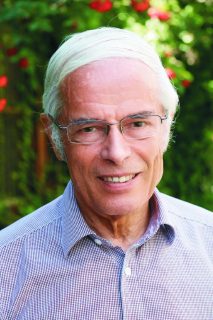

Dr Gábor Náray-Szabó is the president of the board of trustees for József Marek Foundation that took over the operation of the University of Veterinary Medicine as of 1 August this year. He is a chemist and a second-generation member of the Academy of Sciences. He has conducted his research projects and science promotion activities in international cooperation and associations, respectively. Here’s an excerpt from our interview with him.

– You don’t often see father and son both becoming members of the Academy of Sciences – especially in similar scientific areas. I could ask you what your “scientific cradle” was like, but I know that the late 1940s brought a lot of ordeal for the Náray family.

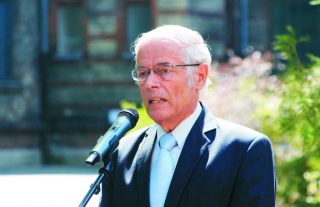

– My father, Dr István Náray-Szabó was a role model and a challenge at the same time. He graduated from the Palatine Joseph University of Polytechnics as a certified chemist. Then he went to Berlin and later to Manchester where he studied X-ray crystallography under Nobel Prize laureate William Lawrence Bragg. Coming back home, he identified the crystal structure of silicates and earned an excellent reputation in the area. Before World War II, he was a leader of the Hungarian Community. This association was founded in order to support Hungarians by giving grants to talented young people typically coming from farming backgrounds. The group was dissolved during the German occupation. Then it was formed again but my father did not return to it. Since the association maintained relations with the Smallholders’ Party, it was falsely accused of conspiracy against the republic, which served as a pretext to cut the Smallholders’ Party into pieces. During the show trials, my father was subpoenaed as a witness in early 1947 (I was 4 at the time) but he indignantly protested against the Hungarian Community’s existence being questioned. He was “promoted” from witness to accused. His initial 3-year sentence was even raised to 4 years and he was also deported for two years. Although he became a corresponding member of the Academy in 1945, he was expelled in 1949 and he was only posthumously rehabilitated in 1989.

– My father, Dr István Náray-Szabó was a role model and a challenge at the same time. He graduated from the Palatine Joseph University of Polytechnics as a certified chemist. Then he went to Berlin and later to Manchester where he studied X-ray crystallography under Nobel Prize laureate William Lawrence Bragg. Coming back home, he identified the crystal structure of silicates and earned an excellent reputation in the area. Before World War II, he was a leader of the Hungarian Community. This association was founded in order to support Hungarians by giving grants to talented young people typically coming from farming backgrounds. The group was dissolved during the German occupation. Then it was formed again but my father did not return to it. Since the association maintained relations with the Smallholders’ Party, it was falsely accused of conspiracy against the republic, which served as a pretext to cut the Smallholders’ Party into pieces. During the show trials, my father was subpoenaed as a witness in early 1947 (I was 4 at the time) but he indignantly protested against the Hungarian Community’s existence being questioned. He was “promoted” from witness to accused. His initial 3-year sentence was even raised to 4 years and he was also deported for two years. Although he became a corresponding member of the Academy in 1945, he was expelled in 1949 and he was only posthumously rehabilitated in 1989.

Thanks to my mother’s tenacious education, I wanted to do my best to show that I’m worthy, too. I had my A-levels in 1961. I was going to apply to ELTE University but the school’s Communist party secretary said the Náray child could not set foot in his institution as long as he was there. So I went to Veszprém where many of my father’s former students were employed. After graduation, I started to work in the Chinoin pharmaceutical factory, then I became a researcher at the Physics Institute of the University of Polytechnics from 1968 to 1970. I was also a research fellow on a Humboldt scholarship in Göttingen in 1971 and 1973. I worked for Chinoin for 18 years from 1972.

– Your father established Hungary’s first X-ray diffraction laboratory, while you are credited for the foundation of our first laboratory for protein crystallography. At first, you were involved in computer-aided molecular design. What does it mean?

– Intuitive pharmaceutical research produces a lot of compounds, “just putting them out there” as my father used to say, and they use trial and error to select the ones that could be effective to treat an illness. Since this method is horrendously expensive, they thought they would try designing molecules. The first mention of rational pharmaceutical design can be traced back to an American publication in the 1960s. I was originally interested in theoretical chemistry, although people urged my father to talk me out of it as there were no computers in Hungary at the time. He couldn’t. I began working with calculations, then my interest gradually turned towards pharmaceutics.

Later on, we were able to identify the spatial structure of larger biomolecules and enzymes. We used X-ray diffraction to map out their highly complex structures, this is where my work was connected to my father’s professional area.

By analyzing the interactions of smaller molecules, we can determine how they influence the functioning of enzymes, for example. For instance, if you inhibit the digestive enzyme of bacteria, they die and the patient recovers from tuberculosis. My work gradually focused more and more on structure-based pharmaceutical research. Consequently, I became increasingly interested in proteins. In the early 90s, we were given the opportunity to apply for funding to set up a fully-equipped protein crystallography lab. I organized a small team and we realized the plan at ELTE University’s Faculty of Sciences because that’s where I got a job as a professor in 1992. The ELTE-Crystallab has been successful ever since. The Academy admitted me as a corresponding and then as a full member in 1990 and 1998, respectively.

– What do you consider as your most significant scientific achievement?

– I’ve always been very interested in proteins, I made various calculations about them. My hypothesis about the operating mechanism of the trypsin enzymes, which play an important role in digestion, coincided with that of American scientist Arieh Warshel who worked in a similar area and whose theory had not yet been accepted at the time. Learning about my research, he invited me to the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. We worked together for three months in 1988 and published a joint article on a tiny detail of the mechanism which we were able to fully clarify. The article was rejected at first but then was met with great response after its release.

– How can the University of Veterinary Medicine benefit from the new operating model?

– With the new operator taking over, we will more or less own all of our accomplishments, but we’ll also be accountable for our failures. I believe it’s an unprecedented intellectual challenge to help a properly funded community of dedicated and internationally acknowledged people to show what they can do if they are given significant freedom to make business management decisions. We have three main resources. The first is the excellent and ambitious student community. The second is the academic capacity of our teachers and researchers. The third is our “money-making” potential lying in the sales of our intellectual products. The biggest challenge is to utilize this potential because Hungarian science tends to avoid taking chances as the benefits of our efforts were always reaped by someone else in the past 500 years. We have to find the right balance between playing safe and taking risks.

Interview and photos by Gusztáv Balázs